Diversification is a misunderstood investment concept, even by many professionals.

Ray Dalio, the founder of hedge fund giant Bridgewater Associates, called it “the holy grail of investing”.

Harry Markowitz, the pioneer behind Modern Portfolio Theory, saw diversification as “the only free lunch in finance” — the only way for investors to reduce portfolio risk without sacrificing return. There is merit in that.

While the importance of diversification is clear, its drawbacks are far less palpable — and easy to miss. Is it truly a free lunch? Is it possible to have too much of a good thing — and be over-diversified? Do you really need to own the entire market? Let’s find out.

How many investments are enough?

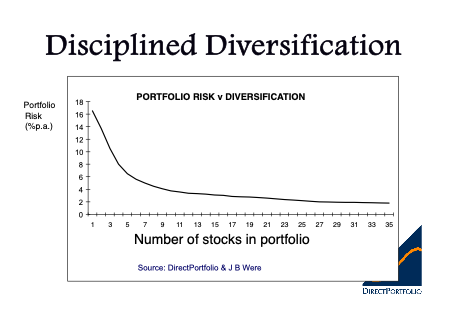

Once upon a time, all fund managers owned hundreds of stocks. These days its understood you only need between 10 and 30 stocks in a portfolio to be properly diversified, though the exact number is up for debate. Liquidity considerations force large fund managers to hold more.

Value investors like Benjamin Graham suggested that 15-30 stocks were enough, while Fisher and Lorie (1970) found that 32 randomly selected, equal-weighted stocks were an excellent option.

When John Aldersley launched ShareInvest in 1994 and DirectPortfolio in 1996, he argued a carefully chosen ten stock equally weighted portfolio could provide sufficient diversification, and this was back-tested by J B Were at the request of RetireInvest and Westpac Investment Mgt who had their doubts – and proven to be correct for the Australian market as the old graphic opposite attests.

There are pragmatic and performance reasons to own fewer stocks. If you hold just 15 names, you can afford to research each company in your portfolio — something that’s impossible to do if you own the 505 components of the S&P 500 or the whole ASX200.

And S&P 500 index funds aren’t that well-diversified anyway. Since the S&P 500 is a capitalisation-weighted index, companies with larger market caps are weighted more heavily. As a result, the top five holdings in the S&P 500 account for nearly 21% of the index, and the top ten components make up nearly a third.

The more stocks in a portfolio, the harder it is to add any value because the portfolio behaves like an index, and there is no conviction in the construction other than a desire to behave like the index.

Diworsification

“Diworsification” — being too diversified

Unfortunately, it is possible to have too many investments in your portfolio.

In his 1989 book “One Up on Wall Street”, legendary investor Peter Lynch expressed disdain for over-diversification. He called it “diworsification” — and noted that past a certain point, sticking additional investments in a portfolio may lead to worse outcomes.

This occurs because diversification isn’t immune from the economic concept of diminishing marginal returns — the insight that the diversifying benefit provided by an investment declines with each additional contribution.

For example, while adding another issue to a four-stock portfolio will do wonders for portfolio diversity, the 50th or 100th stock will contribute essentially nothing — or might even harm the portfolio — since the maximum benefit of diversification has already been acquired.

That said, over-diversification is still preferable to a seriously under-diversified one; while the former risks underperformance, the latter risks ruin.